Benjamin Banneker: A Renaissance Man & an Abolitionist

This story can be found in our book, Stories about Black History: Vol. 2.

Benjamin Banneker was born on November 9, 1731 in what is today Baltimore County, Maryland.

According to accounts his grandmother, Molly Welsh, was a white English woman who was sent to the American colonies as an indentured servant.

After serving her indentured time, she was able to obtain her own property—which was a remarkable thing for a woman to do in the late 1600s. She then purchased enslaved people to work her land...she ended up buying two human beings—one of whom was said to be the son of an African king, whose name was Bannaka.

Molly freed both of the people she bought and married Bannaka. Bannaka was described as a dignified and upstanding man and he and Molly had four daughters.

Their first daughter, Mary, also married a man who was born in Africa—Robert. He was kidnapped in Africa and brought to America, as a slave. He somehow secured his freedom, adopted the first name, Robert, when he was baptized, and married Mary—taking on her last name, now spelled Bannaky.

Robert and Mary Bannaky had four girls and one son—their only son, Benjamin, was born on November 9, 1731. Robert Bannaky was a very resourceful farmer and father and, when Benjamin was just five years old, Robert used 7,000 pounds of tobacco to purchase one hundred acres of land.

The land that Robert Bannaky bought is near this location in Maryland.

Wisely, Robert Bannaky put young Benjamin’s name on the deed, which meant that Benjamin (and his sisters) would most likely not be forced into slavery (and they never were) because their mother, Mary, was born free and their family (Robert and Benjamin) were registered landowners. This was a very smart move by Robert Bannaky.

Early Accomplishments

Benjamin Banneker was a self-taught man (although he probably received some instruction in reading from his grandmother, instruction in astronomy from his father, and some education in arithmetic during his brief stay in school).

Benjamin fell in love with reading, mathematics, literature and any number of subjects. He took as much time as he could to study, in between the time it took for him to run his farm.

When Benjamin was about twenty-one years old, he came across a pocket watch which was a novel gadget at that time.

He was so intrigued by the device that he examined it...studied its inner workings...and created a fully functioning clock, made completely out of wood. This accomplishment obviously took mechanical engineering and mathematics to complete.

The clock, created in 1752, was the first of its kind in America and it kept accurate time for decades.

Banneker also corresponded with mathematicians…some of whom sent him difficult mathematical problems to solve—he would reply with an answer and, in return, send them problems to solve as well.

Banneker, as you can see, was a skilled mathematician—using his calculations he correctly predicted a solar eclipse which occurred in 1789; contrary to the predictions of other well-known mathematicians.

When he met George Ellicott, who was himself a trained mathematician, Banneker and George developed a lifelong friendship. The two spent hours delving into mathematical subjects and discussing the current events of the day. George had a great deal of respect for Benjamin’s abilities and he gave Benjamin books, drafting tools, and other equipment.

Washington

In 1791 Andrew Ellicott, a relative of George Ellicott, headed up a team responsible for surveying the new Federal District Territory (which would become Washington, D.C.). George recommended that Benjamin be assigned to the team. This presented Banneker with an opportunity to work with some of the most advanced surveying equipment, of that time. The team’s job was to survey the ten square-mile area by establishing its boundaries, setting up markers and determining the main streets for the city. Pierre L’Enfant was responsible for designing the city, but Ellicott’s team arrived before L’Enfant and began surveying.

Banneker, who was hired as Andrew Ellicott’s assistant, was responsible for many things; including maintaining the astronomical clock used in the surveying. He had to regularly monitor the rate of the clock by reading the position of the sun in the sky.

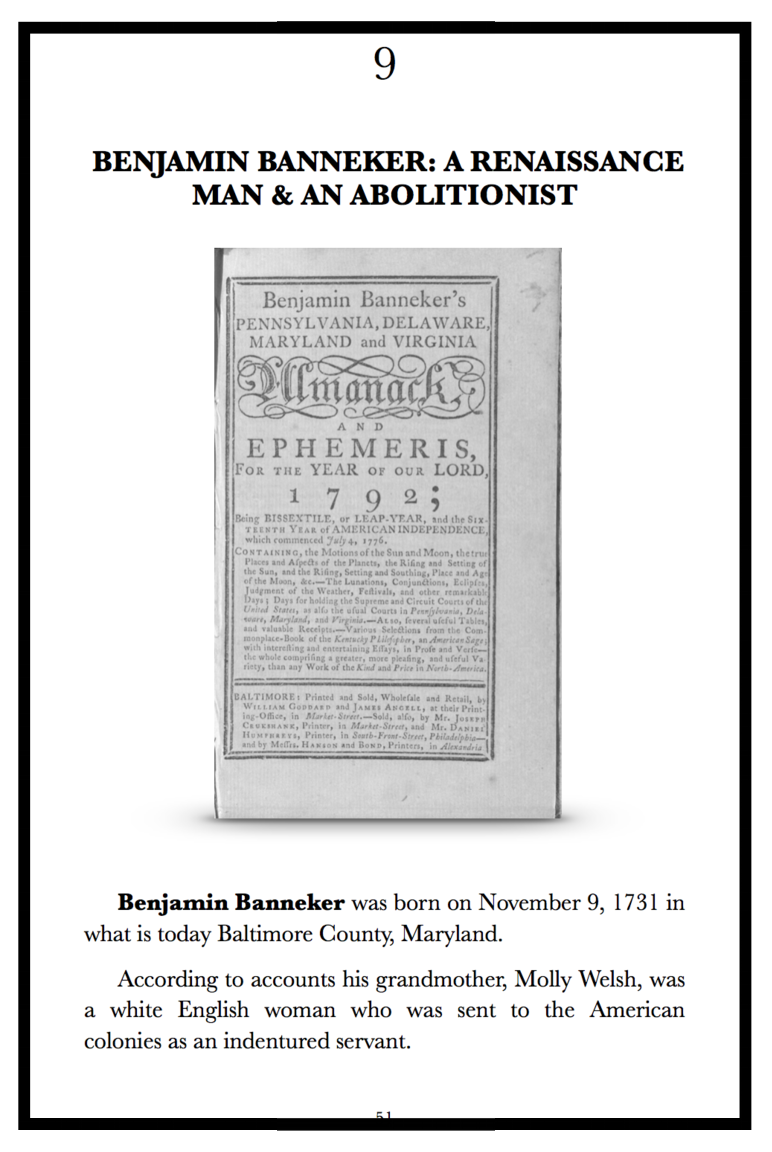

All of this experience, and his lifelong studies, led him to also produce almanacs. Almanacs were very important resources, at the time, because they provided valuable information about the weather, the rising and setting of the sun, tides, and a whole host of other information. Benjamin Banneker published his first almanac in 1792, his series was called Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of Our Lord 1792.

Abolitionist

Banneker’s accomplishments were remarkable when you consider they all took place before, during, and after the Revolutionary War…imagine being a black person and being a mathematician, an author, a farmer of your own land, an astronomer, a naturalist, and a surveyor of what would become the nation’s capital, in the 1700s...in America.

On August 19, 1791, Benjamin Banneker wrote a letter to then secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson.

In his letter, Banneker asked Thomas Jefferson to remember the words,

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal;…”

He told Jefferson that it was pitiable that although he had been convinced of the goodness of God in granting everyone equal privileges and rights, that he would at the same time enslave by fraud and violence so many of Banneker’s brothers.

This was a remarkable thing for a black man to do in 1791—to write such a letter. He intended only to send Thomas Jefferson a copy of his almanac, before it was published, but the evils of slavery so weighed upon his heart that he could not help but write those words as well. He asked Jefferson to put himself in the shoes of enslaved men and women and to remove any prejudices he may have toward them.

Benjamin Banneker died in October of 1806 and long after his death his accomplishments were used as arguments against the institution of slavery.

© 2015 and 2017 Danita Smith, Red and Black Ink, LLC.

References:

Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum. Friends of Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum, Oella, Maryland, 2015.

Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents. Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/declara/declara4.html, accessed 7-2015.

Jefferson Responds to Banneker. American Treasures of the Library of Congress. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/trr022.html, accessed 7-2015.

Mathematician and Astronomer Benjamin Banneker Was Born November 9, 1731. America’s Story from America’s Library. http://www.americaslibrary.gov/jb/colonial/jb_colonial_banneker_1.html, accessed 7-2015.

Tyson, Martha Ellicott (1795 - 1873), A Sketch of the Life of Benjamin Banneker; from notes taken in 1836. Maryland Historical Society, 1854, read by J. Saurin Norris, before the MHS, October 5, 1854.

Photos:

Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of Our Lord 1792. Created and published in Baltimore: William Goddard and James Angell, 1791. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division. Digital ID, rbcmisc ody0214.