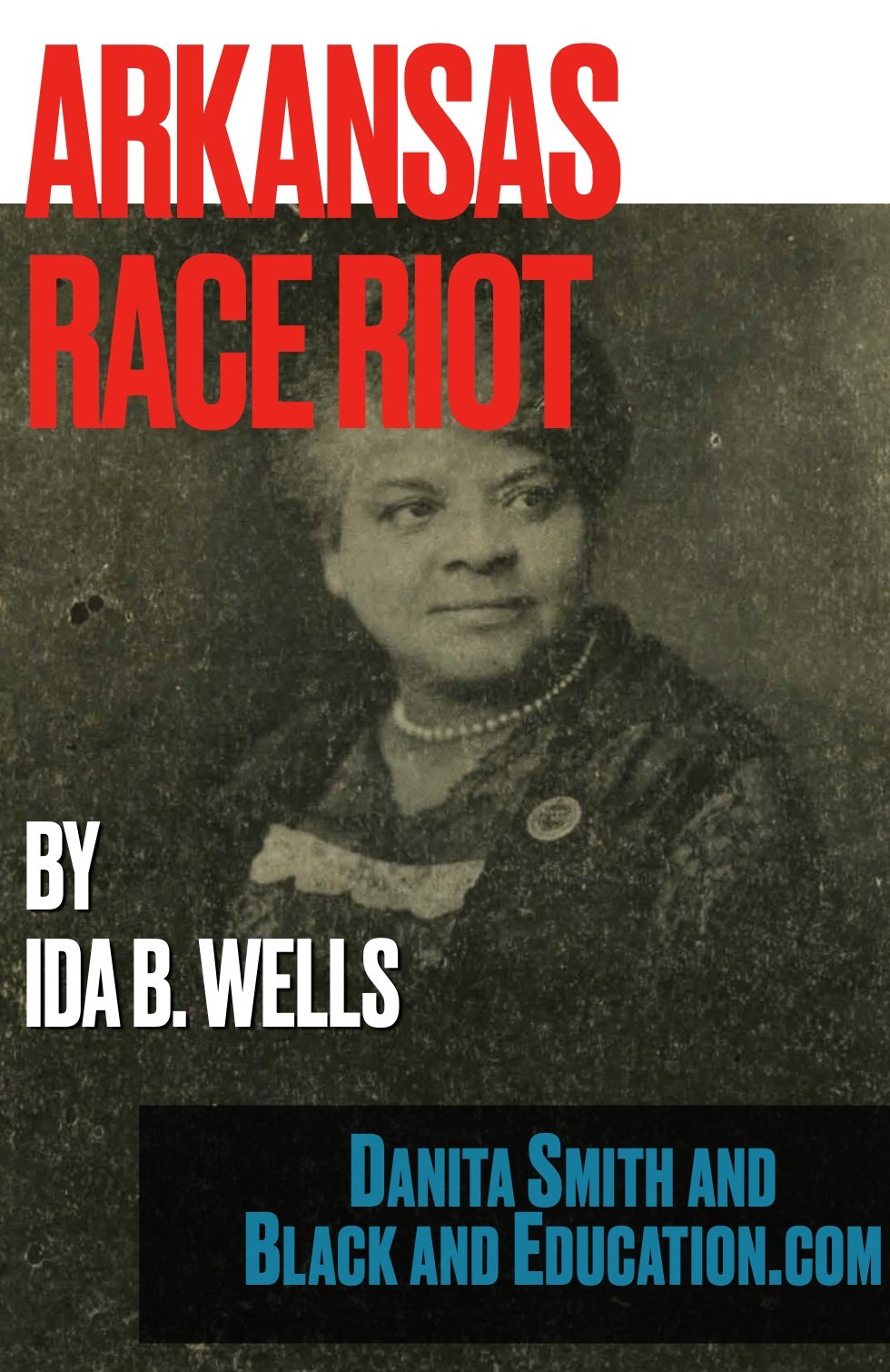

Arkansas Riot 1919 by Ida B. Wells

Subscribe to us on:

The Arkansas Race Riot, by Ida B. Wells-Barnett, May 15, 1920

“Economic justice reached its awful climax in 1919 in the final answer to two appeals made by working men, both groups seeking through peaceful appeal to win better wage and working conditions; both presenting their grievances through chosen representatives, one to be rewarded by the President of the United States with patient hearing and final success, the other to suffer massacre at the hands of the mob and the death penalty by courts of law.

“The first group of working men was composed of the coal miners whose appeal merged into a strike, the second group was composed of colored farmers, whose appeal was forestalled by a conspiracy against them, which, formed among white land owners, to perpetuate the peonage complained against, put to death by lynch law scores of colored farmers and then prostituted the process of courts to their purpose, sent seventy-five working men to the penitentiary for long terms of imprisonment, and doomed twelve to die in the electric chair.

“The bare statement of these facts is so shocking to the sense of justice that it almost defies belief, but the statement finds its complete corroboration in the burnt and pillaged homes of the helpless colored farmers exiled or murdered and the ninety victims who in hopeless despair look through the penitentiary bars, twelve of them sentenced to death because they dared, in this democracy of ours, to ask relief from economic slavery.

“The circumstances attending the two appeals were almost as remarkable as were the final and widely differing results. The miners made their appeals for higher wages accompanying them with the implied threat of a strike. That appeal was made to the Federal Government and was accorded a full and patient hearing. Representative labor leaders were heard by chosen representatives of the Government, who granted relief in some cases and denied it in others. The miners, dissatisfied, retired from the conference to determine further action.

“Quick action by miners unions followed the report of the miner leaders. A strike vote was called, and in overwhelming numbers the miners decided to strike. The disastrous result of the proposed strike caused the government to counsel against the militant methods threatened by the miners and even the President of the United States from his sick bed sent his appeal to the strikers in the interest of peace.

“But the miners turned deaf ears to that appeal, closed their eyes to the disastrous results of the impending strife, and boasting of their power to throttle the nation into submission, went on a nation-wide strike and for a period of ten days crippled transportation, deprived the public of food, shut off lights, banked fires, thus threatening to freeze the helpless public, and spread misery over every part of American soil. Court injunctions were ignored and the Government, helpless, yielded, and the President capitulated to the strikers. The strike leaders, triumphant, called off the strike and the miners' appeal was rewarded with success.

“Shortly preceding these eventful days, another group of laborers decided to make their appeal for better wages and working conditions. They had suffered conditions which denied them freedom to make fair contracts, forced them to buy at exorbitant prices and sell their produce at rates amounting almost to confiscation. Land tilled on shares barely brought the farmers money enough to pay their "findings," supplied by the white land owner, leaving the toiler a pittance of his year's work, often leaving him in debt.

“The Negro farmer hoped to share in the increased price of cotton and the general prosperity of the Nation, and all during 1919 looked forward to a bountiful reward at harvest time. Cotton, which in former years had sold for twelve and fourteen cents a pound, had gone to forty-five cents and higher. The sunshine of "Great Expectations" brightened the cabin homes. But when harvest time came, the farmers' dream failed, for profiteering land owners combined and no forty-five-cent prices were to be had. Farmers who would sell their cotton for twenty-five cents were paid the price. Those who demanded the market price were unable to sell. Naturally widespread unrest followed. The farmers resented the imposition of the cotton buyers, and the buyers denounced the "darkies" who dared to demand a square deal.

“Meanwhile, the Negro farmers decided to combine their forces and employ a white lawyer to represent them in their plea for better systems of contract, better wages, and better working conditions. The result was an organization which was of the nature of a secret fraternal order.

“The farmers joined the lodge rapidly and the section in and around Elaine was represented by nearly two hundred farmers. The meeting places were the colored churches at Elaine and Hoop Spur. Only three meetings had been held — two of them before the day of the "slaughter of innocents," which was the 30th day of September, 1919. The lodge employed Mr. Bratton, a white lawyer, to represent the members in their effort to secure the market price for their cotton, to arrange for better contracts, to adjust their accounts with the landowners and generally to safeguard their interests.

“This labor movement among colored farmers did not please the white landowners and the proposal of the farmers to act through a white lawyer constituted a menace to the profiteering practices of the white people of the neighborhood. The dissatisfaction of the white people found expression at first in gentle hints that the Negroes were making a mistake; these were followed by warnings to colored people to let that lodge business alone. Colored men knew of the success of white men in labor movements, and, believing they would be protected by law, continued their plans for presenting their claims.

“Then came the tragedy such as no labor movement in this country has ever witnessed. On the night of September 30th, while the lodge was in session at the church in Elaine, about 150 men, women and children being present, five automobile loads of white men stopped in front of the church and immediately fired a volley of shots into the building. The people rushed out only to meet volley after volley from the white mob. Several persons were killed, the others ran to the woods or made their way home. One white man was shot, but whether he was killed accidentally by one of his fellow lynchers or was shot by some Negro during the fight is not known.

“Next day white men from all over Phillips County and even from Mississippi set the church on fire, burning up several persons who were killed the night before, and then began a systematic man-hunt, killing colored men indiscriminately, driving others from their homes, and then taking from these abandoned homes the produce saved by the farmers for their winter use. Thousands of dollars worth of property was destroyed and stolen and cotton by the bale which the farmers had refused to sell was boldly carted away by members of the mob.

“Next followed an even more deplorable act of this Arkansas tragedy. Upon pretense that the white man who was killed on the night of the riot, and also the two next day were the victims of a conspiracy formed by colored people to kill all the white people, over one hundred colored men were arrested and thrown into jail. While they were thus confined their homes were robbed of every bit of property, so that when those who were set at liberty, upon their promise not to join the lodge again returned, they were without food, shelter or clothes!

“To contrast the result of the plea of the miners for better wages, with the results of the plea of the Arkansas colored farmers for identically the same thing, is to disclose to thinking people a phase of democracy not safe for the world or any part of it. The miners combined in unions, counseled together and chose representatives to present their pleas which carried the threat of a strike. Their demands were not granted and ignoring the President's appeal, they struck. Their strike menaced the lives, health, comfort and welfare of the entire nation. They defied the courts and brought the President to his knees. He yielded, the strike was won and the miners came into their own.

“The colored farmers combined, counseled together, employed counsel to present their plea. They did not threaten to strike, did not strike, menaced nothing, injured nobody, and yet:

“Hundreds of them today are penniless, "Refugees from pillaged homes";

“More than a hundred were killed by white mobs, for which not one white man has been arrested;

“Seventy-five men are serving life sentences in the penitentiary, and

“Twelve men are sentenced to die.

“If this is democracy, what is bolshevism?”